To listen to the podcast, click here.

Mental health struggles and addiction are more common than we realize, especially among attorneys. In this episode, Brian Cuban, author of The Addicted Lawyer: Tales of the Bar, Booze, Blow, and Redemption, delves into addiction and the recovery journey for lawyers. As an advocate for mental health awareness and recovery, Brian shares his personal story, which includes psychiatric struggles, in-patient treatment facilities, and jail. He also covers his experience as an author and his shift into writing fiction. Tune in to this inspiring episode for a roadmap to finding the point of acceptance and a positive path forward.

Our guest is someone who's probably familiar to a lot of our readers either through State Bar things or social media. It is attorney, author, and advocate Brian Cuban. Brian, thank you so much for joining us.

Thanks for having me. It's full disclosure. I think the last appellate brief I wrote was in law school.

The good news is you don't have to be an appellate lawyer to be on our show. In fact, our audience probably get a little tired of hearing appellate lawyers over and over again. We try and change it up. Attorney of mental health and wellness is one of the side topics that we like to cover a lot and you're someone who we've wanted to have on for a long time on that.

I appreciate it.

For our readers, probably a lot of them are familiar, but for those who aren't or maybe those who don't know your backstory, can you tell us a little bit about your background and who you are?

My name is Brian Cuban. I'm a graduate of Pitt Law. I was a 1986 grad. I was not licensed in Pennsylvania anymore. I'm considered retired there, but I am licensed in Texas. I was born and raised in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. I am a Baby Boomer. I'm the middle of three boys. People know my older brother, Mark, and I have a young brother, Jeff. I went to Penn State before Pitt Law. After that, I moved to Dallas where I became an "ambulance chaser."

After failing the bar two and a half times because back then, they split it up into parts. You could pass one and fail another and not have to retake it. I have no idea what it's like now. Those failures were related to drugs and alcohol. I finally became a lawyer and became an unethical and awful lawyer and every Saul Goodman stereotype there was except aiding drug cartels. It's probably something I was engaged in at one point or another.

I don't say that as a point of honor or as a badge of honor, but if you open the Texas Bar Journal, which some lawyers ignominiously refer to as the Pages of Shame, at the back, if you look at the list of lawyers who are disbarred and suspended, a good portion of those are going to be related to drug, alcohol, or other mental health issue. During that time in Dallas, I became addicted to cocaine as well as alcohol. I developed significant mental health issues that led to a trip to a psychiatric facility. I went to jail for DWI with three failed marriages. I lost my career as a lawyer. I went to work for my brother and that didn't work out well either because I was blowing and going literally.

Finally, after my second trip to a psychiatric facility, I began my journey forward into recovery. That was on Easter weekend in 2007. During that time as a litigator, it was ridiculous for me to call myself that because I would show up to court high. I was doing cocaine in the federal courthouse bathroom, the state courthouse, and the George Allen Courthouse bathroom. I was showing up to hearings under the influence of cocaine or Valium.

People might say, "Didn't you know that was wrong?" I had an addiction. I wasn't stupid. I knew it was wrong, but that's the definition of addiction, an obsessive-compulsive drug-seeking and youth behavior in the face of known and probable consequences. Yes, I know it was wrong. Do lawyers know they can get fired when they're using, knowing there are ops at the door, or they're showing up for work drunk or hungover, or whatever the issue is? Of course, they know that, but it's addiction.

It's beyond your control. Is that what you're getting at?

The brain disorder in terms of what addiction is and what it isn't. We get that it's an addiction of choice. You hear that all the time. When I was in the bathroom of the Crescent Hotel back when it was called here in Dallas, back when there was a bar called Beau Nash, I was in the basement of the hotel and I did my first line of cocaine. It was a choice that was predicated on a lot of self-image issues and a lot of other mental health issues I had going on that I needed to feel good about myself and chose a destructive way to do it.

What happened after that wasn't a choice. The rewiring of my brain resulted in me needing this because I very quickly became psychologically dependent on this artificial feeling of looking in the mirror for the first time in my life while I was high and loving myself. I did my first line of cocaine in that bathroom down at the Crescent Hotel and I looked in that mirror and said, "Yes, baby." At 24 years old or 25, for the first time in my life, I loved myself.

I had a lot of childhood trauma in my life, or at least what I did find as childhood trauma. That feeling became something I incessantly needed, but the cocaine high doesn't last very long. I use alcohol to suppress the feeling of not loving myself. If I couldn't feel good, I wouldn't feel at all. These two things, the alcohol and the cocaine became intertwined and became that ever-growing snowball rolling forward in my life to this giant boulder that was taking out everyone and anything around me as I rolled forward like marriages, family relationships, and my career. It was leaving a swath of destruction.

I want to back up for a minute based on something you said and please don't feel compelled to share too much or anything, but you mentioned childhood trauma. A lot of people at a certain age don't recognize the connection between adverse childhood experiences and trauma to later addiction. There are loads of literature and studies on that. When did you first notice your struggles or have you had them your whole life?

That's a great question because, to understand my journey through mental health and addiction, you have to understand my childhood. People can debate the strength of the correlations between childhood trauma or trauma in general and mental health issues. When we talk about trauma, I'm not talking about the textbook understanding of PTSD that people have where you go to war and this happens or that happens.

There are many kinds of trauma and trauma is unique to the individual. What I view as trauma that impacts my life negatively, another person raised in a different way in different social and environmental factors may just shrug that off. They say, "It wouldn't bother me," whether it's bullying or something like that. Let's take the time machine back to Pittsburgh, PA. I was growing up in the early '70s Baby Boomer. I'm the middle of three boys.

Mark was the oldest and Jeff the youngest. Mark as the firstborn with very outgoing. It was something you might expect in a Dr. Spock book on childhood development. He was outgoing and very entrepreneurial. He was selling this and that door to door with his team. I remember our local newspaper went on strike to both of them. He and his buddies who are barely old enough to drive made their way out to Cleveland. They bought the Cleveland Plain Dealer. It was about 200 miles. They brought them back to Pittsburgh and sold them in downtown Pittsburgh during rush hour for twice what they paid. You kind of knew what he could be.

My younger brother, Jeff, was a good-looking kid. He is a naturally ranked wrestler and a jock, the beer parties, the dates, the prom, and the girlfriend. It is all the things I associated with love and peer acceptance. I had classic Middle Child syndrome to the extent that people believe that exists in the Dr. Spock hierarchy. I was shy. I was withdrawn. I internalized anything negative that was said about me. That's who I was. I like a skin-tight suit.

I was a heavy kid trending towards obesity. Unfortunately, I also had a very difficult relationship with my mother. For everyone who reads this, I want to make it clear that I do not blame my mother or my father for any mental health issue I went through later in my life. Parents do not cause addiction. Parents do not cause eating disorders. The people reading this can have a general understanding, and if you don't look it up, cause and correlations are not the same.

Trauma and the things that happen in the home can correlate with mental health issues later in life. It'll happen to some people, and it won't happen to others. That's why we say correlation. It's not going to happen to everyone. There was a lot of fat shaming in my house. I used to come home from school for lunch and I pulled open the cupboard. I pull out the can of Chef Boyardee, Beefaroni, and SpaghettiOs.

They still have that. I took the old-style can opener because we didn't have an electronic can opener. We didn't have a microwave to stick the food in. I wouldn't even heat it. I just stick the spoon in and gobble it up. My mom would come home from selling real estate and she would walk into the kitchen, and not all the time, but it happened enough that it was traumatic. She would say, "Brian, if you keep eating that way, you're going to be a fat pig"

These were the things that my grandmother said to my mom. I have no doubt these were the kind of words that were spoken to my grandmother. I have Jewish grandparents who came from Lithuania. They struggled with food. It was the stereotypical Jewish grandparent. My grandmother was also a diagnosed schizophrenic according to my mother. My mom and my grandmother had a very verbally and mentally abusive relationship with each other. It was awful to witness as a young boy the things they said and did to each other.

Fat shaming often runs downhill generationally in families. My mother was someone at the time who was struggling with her own mental health issues. She had a nervous breakdown. She had spent some time in a mental health facility. I didn't understand any of this as a kid. When she was gone, I didn't know where she was. Hearing these things, you grow depressed. You're hearing them from your mother. I began to eat more Chef Boyardee.

I became a bigger Brian. It so often happens when you change what other kids perceive negatively in high school. The bullying became worse. I was already bullied to some extent, but it became much worse. "Brian, you're a fat pig." You must have talked to my mother. "Brian this, Brian that. You need to get a bra for your man boob."

I became the sad clown. This was before Al Gore invented the internet. I didn't have these images of perfection. My images were the people I saw every day, the people who were going to the after-school parties, the people who were going to the football games together, and the people who were going to the McDonald's to hang out in the cars and all the prom kings and the prom queens. In my mind, they were all thin and good-looking.

These were the images I wanted to be like, the kids who are getting their first kiss and walking down between the lockers holding hands. I was experiencing none of that and, in my mind, was not deserving of any of that. I wouldn't even bother asking a girl to the prom because, in my mind, she was going to call me a fat pig. I was isolated and I spent my time mostly in my bedroom playing games and doing different things. I was isolated very severely.

All the bullying culminated in what I call the day the gold shined. We have to go back in that time machine to the disco around 1976 when I was a freshman in high school and Saturday Night Fever movie had just come out. For those who don't know, John Travolta got the disco craze going back then. For all of your Gen X-ers, you are going to have to go look up Saturday Night Fever probably.

John Travolta started this movie and he wore these very tight pants. Mark would disco in Downtown Pittsburgh. He wore the same types of pants, platform shoes, and bell bottoms. One day, he walked into my room holding up a pair of shiny gold satin disco pants. He goes, "Brian, here, you can have these. I am buying some new ones." I said, "Great." I love my brother and he gave them to me, but Mark wasn't a big guy. They fit him fine. I had to jump up and down and spray the water bottle. My butt looked like fifteen cats trying to get out when I finally got in there and stretched them around my gut.

I went to school wearing these pants. My gut hung over. My butt was bubbly and the kids made fun of me. I felt deprecated to shut them off. One day, I'm wearing my shiny gold bell-bottom disco pants and I'm walking home with this group of kids. In my mind, it was the popular kid who I hung around. I worked on the outside of their circle hoping that it would be like a fraternity hazing where one day they'd say, "Put the arms around me."

That's what they called me. "You're one of us now. You can come to the concert. We're going to see Cheap Trick." We're about a mile from my house. They're making fun. All of a sudden, one of the kids reached out across and pulled on the zipper which was already tight and bulging. It rips a little bit right down the zipper line.

Another kid goes, "Whoa," and he pulls and it rips some more and tears. Now, my underwear is visible. They were on me like a pack of rabid dogs. They tore my pants off and ripped it into shreds. We were out in a busy street with cars whizzing by out of my Fruit of the Loom tighty whities, my Pittsburgh Pirates t-shirt, my three-ring tube socks, and tennis shoes. You are both still too young to remember the three-ring tube socks. They walked on high-fiving like they had done the greatest thing ever.

I go out in the street, I pick up the shreds, and I put them over my underwear. I waddle home. I'm waddling toward my house and I might as well have been walking to China. That's how far away my house seems in this ultimate walk of shame. I vividly remember the worst part. The heart-stopping shame was at the stoplight. I was standing at these stoplights of a busy road I couldn't even run across. These cars would stop, looking at me. No one said anything. They would go on.

I finally got home. The house is empty. I go down into our basement. I remember the blue-painted wooden stairs. With every step, all of a sudden, it creaks. I never noticed the creak before. Every step creaks as I walk. I even tried to tiptoe, but there were these creaks that seemed to reverberate like ripples on the water going out to where my father fixed cars. He would know my shame and go out to my brother wherever they were. "Dude, you couldn't stand up for yourself?" I was going up to my mother selling real estate, "I told you so," when she would have said she loved me dearly. She was struggling with her own things.

They all would have loved me. That is how deep the shame and trauma was. I found a waste basket and I shoved those shreds at the bottom of the Chef Boyardee Ravioli cans, the newspapers, and whatever else was in there thinking that I would never speak of this again. If I hid those shreds, it would hide my shame. When the garbage man took away the wastebasket, it would take away my shame, but that's not how trauma works.

Trauma remembers. It has a way of percolating out when we think we've forgotten all about it at the times we least expect, and it's rarely in a positive way. When we talk about bright line moments or snapshots of our lives or snapshots of trauma, that was obviously a big one. It was around then that I remember, for the first time in my life, looking in the bathroom mirror and thinking something different.

Addiction: Trauma has a way of circulating out when we think we have forgotten all about it.

I was not seeing Brian anymore. I saw a fat pig and a monster who would never have a girlfriend, never get married, never have a friend, and never be loved by his mother again who loved me dearly. I wasn't worthy of anything and deserved all of the vitriol that I was about to inflict on myself because I must punish myself for being a fat pig. That's where it started.

It's amazing the level of detail that you can recall about those events and how they impacted you.

Let's talk about that because we also have to remember. My psychiatrist or therapist says all the time when we talk about these things that memories are just memories of memories. We remember feelings and general events. If we had the Hot Tub Time Machine and I was to take that back to Pittsburgh, PA, it is like eyewitness testimony. Can I put my hand on the Bible or whatever in a courtroom and say that's exactly what happened? Of course not because, as we age, our brain fills in detail. That's how we challenge eyewitness testimony. Our brain fills in things as we forget things to make up for that. I believe that's how it happened, but beyond a reasonable doubt, of course not.

No one's going to hold you to that standard here, Brian. It's a compelling story regardless. We do appreciate you sharing that.

From that, is that when your addiction journey started or was that well later?

It's when I graduated high school with moderate drinking. I went on to Penn State University. I was also suffering from bulimia. A lot of people may not realize that guys do get eating disorders just like females and other genders whether it's he, she, or they, however we refer to ourselves. I developed bulimia in '79 going to '80 as a freshman at Penn State back when no one was talking about eating disorders for men or women.

If you remember the wonderful golden-voiced singer Karen Carpenter, who is a wonderful drummer. She developed anorexia and passed away from complications in 1983. This was years before that. She brought eating disorders into the pre-digital national spotlight that cemented to stereotype females where it's a female disorder. That's false. If you look at the stats, it'll say about 35%, but if you talk to professionals, up to 50% with eating disorders are male, but only 1 in 10 will take treatment because of the shame and the stigma. Also, the lack of available resources because of the stereotype, shame, and stigma. I wanted to touch on that.

I began drinking heavily at Penn State. I was at Penn State where I would have been first classified as an "alcoholic" if I had sought help. It is the clinical diagnosis of alcohol use disorder. An alcoholic is a legal profession-friendly term. We are a 12-step-friendly profession. For those who don't know, AA is the most well-known, but there are other 12-Step groups. I was not in any of that at Penn State.

I remember I was going to class drunk. I was drinking alone. Again, I was isolating. I didn't have any friends that I remember. I would go out at night. When I turned 21, I would hit the state stores. That's what we have in Pennsylvania. The government still controls the liquor industry and, to some extent, the hard liquor industry. I would buy these little bottles of tequila. I wear cowboy boots so I can steal the tequila.

I would go out into the alley where all the bars were out of Penn State and State College. I would down this tequila to get drunk before I even walked into the bar, hoping that it would allow me to be someone different. All that would happen in the bar is I would drink more and I wouldn't talk to anyone. The drinking would cause me to shrink more into my cocoon. I would leave a complete mess, drunk, and feel validated that I was a loser and a monster. I was not worthy of it because I couldn't bring myself to talk to anyone and no one talked to me.

I remember my eating disorder. I would go buy a large pizza or a 2-pound bag of peanut M&Ms and binge and purge in the alley. I was not telling anyone. The closest I ever came to any epiphany was I have a drinking problem at Penn State. There was never an eating disorder epiphany because it wasn't talked about. I'd walk into a place. I think it was a hamburger joint. I can't recall the name of it. It might have been White Castle.

I came across a rack of pamphlets at the 12-Step groups put out. It was called The Twenty Questions. I don't know if they still do it now, but at that time, they were in the bars and the hamburger joints and things like that. It was geared towards college students. You pass out, you miss class, and you black out. I'm checking off yes to all these things mentally. I thought to myself, "I'm just a college student. We all do this." I toss it in the waste basket. That was the closest I ever came.

I was a Criminal Justice major at Penn State. I wanted to be a cop. That would have worked out well. I would have been the first guy in the evidence room trading out the mannitol for the blow, the baby laxative. Also, the Cuban connection instead of the French connection. I'm sitting in the placement at Penn State. I was able to do well because it's straight percentage grading. It wasn't a hard major. I would pull an all-nighter and pull together before every exam. I got decent grades. I had that ability. I'm sitting in the placement office looking through police officer jobs and these little pamphlets before computers.

They would mail them and we would look and see what jobs are available around the country. You would apply for those jobs. There are two guys sitting next to me. The guys I know from the major were from Pittsburgh and they're talking about taking the Law School Admission Test and applying the Pitt Law hoping they get into Pitt Law. I close the pamphlet. I inched closer. I'm listening and the bell starts going off in my head. It's not the bells of, "I want to be a lawyer. I want to be the next Clarence Darrow. I want to emulate Atticus Finch."

It was the bells of, "Law school is three years. If I go to law school instead of entering the workforce, I can drink. I can binge and purge." I had also developed exercise bulimia, which is obsessive-compulsive exercise for the purpose of offsetting calories. I was running up to 20 miles a day instead of going to class, in addition to binging, purging, and drinking. It was a tremendous strain on my body.

All of these behaviors at that point were my security blanket. My line is a security blanket of behavior that no one was going to take away from me. If I went to a law school, I would be able to hold on to that security blanket of behaviors for three more years because my life at that point was not thinking three years out. "I'm going to be a lawyer. I'm going to do this and that." I was thinking at the tip of my nose to survive and get forward. For that reason and that reason alone, it made perfect sense for me to take the LSAT. That's it.

You are talking about all the things that you describe that you did. I'm amazed because you hear the phrase the functioning alcoholic. You mentioned how you're able to do well in school. Maybe this is jumping ahead a little bit, but I'm amazed at how someone can do that.

Let's talk about it well as compared to what. We can talk about this now. I barely survived law school. Well as compared to what standard. There is something I call the Peter Principle of Addiction in the legal profession. You can probably apply to any other job. The Peter Principle is basically working in organizations that will work your way up to your level of incompetence. Theoretically, at that point, we absorb more information. We learn we learn the things we need to learn, we increase our knowledge level, and we keep rising in the organization.

Most people learn that concept and behavioral organization class or whatever. When substance use disorder is involved, whether it's alcohol for a lawyer, a cocaine, or whatever we're talking about like opioids, what happens is the level of incompetent people would keep dropping. Let's say you're a solo, a big law, or boutique. You're giving a buck for a buck at full throttle or $1.25. You're working. You are fifteen hours of the day. Let's say in your mind you're giving it. You're going $1.25 for the dollar. It's because you're giving and going fifteen hours a day, they're drinking a little more and a little more. The level of incompetence keeps dropping and dropping. I can tell myself I am still giving $1 for a dollar, but now I'm only given $0.75 for a dollar.

What happened is I didn't say, "This isn't right," because no one else was saying anything to me yet. I haven't malpractice anything. I haven't missed a hearing. I got that huge truck accident verdict or this verdict. Everyone's looking and saying he is okay, but the reality is I'm only giving $0.60 for a buck. It's because no one's saying anything, I'm kneeling under that new threshold on myself if I'm giving $1 for a dollar. That is the principle of addiction.

As that threshold keeps lowering and lowering, finally, malpractice. Something said something. You're giving $0.50 for a buck. The client says something. Now, your career is in jeopardy. Now, there's a problem. Maybe the state bar is involved because you've done something beyond just malpractice. Maybe you lose your job or you go into treatment or whatever. There are consequences. That's the Peter Principle of Addiction. When we come to substance use disorder, there's no such thing as a high-functioning lawyer. There's only a degree of law. That's where all that was leading. It was a roundabout.

Addiction: When it comes to substance use disorder, there's no such thing as a high-functioning lawyer.

That's a great context to put that in because from the outside looking in, it does seem like someone is functioning on a high level, but the reality is they're functioning on a level but compared to what.

Ask them what's going on with their wife and kids. Ask them what's going on in other pillars of a high-functioning life. Maybe all you see is this, unless you're the best friend of this person, you're a colleague and you're intertwined with what's going on in the family and things like that. If you go to SAMHSA's website and look at their definition of recovery, it says nothing about sobriety. It talks about all these pillars of a good life, work, family, and friends. All of these different pillars of leading your best life. What you see is only one pillar, and that person may be expending every ounce of energy he, she, or they have to maintain that one pillar that you see. It can be very deceiving.

I do want to talk about recovery a little bit, now that you bring that up. Whether it's more generally or your journey, how do you get to that point or did someone drag you there?

It's different for everyone. There is an axiom that you can't make someone do what they're not ready to do. I do believe that everyone, on a general level, has to be ready to some degree because unless you're a minor and have a parental relationship, you can't force someone into treatment. You can force if someone's a danger to themselves or others, which my brother is trying to do to me, but I was too smart for him.

It was my first trip to a psychiatric hospital after I nearly killed myself with a weapon. That was down in Medical City Green Oaks here in Dallas. You can't make someone do what they're not ready to do. You can lay the roadwork. You can lay the path. Sometimes, it's a question of how much damage they're going to be until they're ready. Believe me. Working with lawyers and law students, I see it all the time.

The trick becomes, "What kind of conversation can you have that is not judgmental and forceful in terms of trying to dictate that triggers that one thing that they grab onto and say to themselves because they have to say that to themselves," not you and not to me, "I'm ready." If we could figure that out, we'd all win the Nobel Prize for recovery. I'm not an interventionist. I don't have a degree or anything, but I talk to people.

I refer people to those with degrees. I've referred people to interventionists and to treatment. They've died. Some are lawyers you may know or I know. There was a lawyer in Pittsburgh. It was tragic. I went to his house with this family and we tried to get him an intervention. He's gone. There's no blueprint. What can we do? We can be that compassionate community. Educate ourselves so that when they are ready, we can help. How do we do that? In the legal profession, we have TLAP. Every state has it.

It's the Texas Lawyers' Assistance Program.

Do you know what's funny? I talk to lawyers who, to this day, I have to explain to them what it is. I've talked to lawyers whose only exposure to TLAP was maybe the law firm they went to. They got the pamphlet. They took a CLE because they heard about it and law school, which I'm sure they did. Beyond that, they don't have any understanding. I've talked to lawyers who are afraid to make a call to a colleague because they think it's going to get back to the caller that they ratted them out.

It's not true. It's all confidential. They don't ask who your name is. You can even text. There are all these stereotypes and stigma around what's a norm of the State Bar. I remember when I first started talking. I spoke to the Dallas Bar. I was talking about TLAP and after I came out, after it ended, a seasoned litigation attorney came up to me. He pulled me aside. He said, "Brian, I know what you said, but I'm telling you it's not confidential. I just know." "How do you know?" "Another guy told me." "How does he know?" "I don't know. I think he knew a guy."

You're a seasoned trial lawyer and you're coming to me with a guy told a guy who told a guy. It's not confidential. That is the definition of stigma. I urge people to learn about TLAP and I urge lawyers that it is an act of concern and compassion to call TLAP. They may already be aware of your colleague, your friend, or that lawyer you saw stagger. It may not even be what you think. There could be something else going on.

It's not a judgmental thing to make that call. "What if I'm wrong and it's some other issue?" then you're wrong, but it's never going to get back to anyone that you were wrong. You making these calls and it's an act of compassion. It's act of empathy. It's an act of concern. It's also an act of caring about our profession because once it gets to the State Bar, that's a different ballgame.

As an attorney or a practitioner, what are the signs that would inform you to think, "Maybe I do need to make a call?"

They are going to be different from everyone. There are certain standards and it's all also going to depend on where you are. If you're a solo, except when you're in the courtroom, there may be not a lot of contact with the outside profession, which is another problem. The isolation causes a lot of these, especially during the pandemic. We've seen within the solos drinking pick up, especially for women.

A study done by Patrick Krill of the Californian, DC Bar found that during the pandemic, drinking picked up predominantly in the segment of women lawyers or female lawyers. Lawyers are missing hearing. Lawyers who were kempt are suddenly unkempt. Voicemails are a huge red flag. Somebody is full voicemail. There are obvious signs. You're in and the guy is staggering.

People get breathalyzed in the courtroom. I know lawyers who have pulled other lawyers that they don't know very well aside and said, "I see this. I don't know if the judge sees this. You get help now before it becomes an issue that's out of your control in terms of the State Bar." I have ethical obligations here. That's a whole other issue.

There are standard signs. What can happen is a lawyer could talk herself out of it and say, "I'm not sure. What if she or they yell at me? What if I'm wrong?" You don't have to go up to a person and say, "You're drinking or this or that." If you are familiar with Terry, a criminal defense lawyer who talked about often what's called the two ask. Go up to your colleague. "How are you doing? Is everything okay? I noticed that you seem to be off?" You don't have to accuse them of anything. The response may be, "I'm fine. I'm okay." Before that conversation breaks, you say, "Do you know that if you are struggling, you don't have anyone, and you want to come to me or a complete stranger maybe, sometimes those are the best people to go to because you're afraid it'll get back. I'm there for you."

You can even add the third ask if you're truly worried. "Tell me truly what's going on. How are you doing?" if you think there is something that emphasis may trigger. What you've done is you've become a cog in a continuum of wellness where if we all practice this act of empathy and asking these questions, it may not take all the first time, but it may take hold the second time because now they're thinking about it. It may take hold the third time. You have laid a path to being ready because you have to be ready if they want to walk that path.

You might be the person who finally tips the scale.

You might be the person who finally did it and you may never know that you saved a career and a life because our profession is in crisis. It is a crisis. There has been a quantum leap-jumping awareness with the ABAs. Whatever you think of the ABA, forget that. The legal wellness and issues they have done are wonderful. The protocols they have suggested for firms and the wellness pledge, whether it's a big law, small law, boutique law, midsize, and all those government corporations, they have laid out great frameworks.

Does that mean everyone's going to take advantage of it? Does that mean employers are walking the walk? Not necessarily. I've spoken at many big law firms and I'll get an email from an associate saying, "That's all well and great, but they're having me doing this and this. When it doesn't need to be done, this, this, and that." They are not walking the walk they claim. We have to deal with that. We have to deal with culture. Those are long conversations about whether its culture is keeping up and about while its culture is changing proportionately through these structures that have been put in place. If you took an anonymous poll, the majority of the profession would say no.

Anecdotally, that has been my experience as well because there still is a significant stigma attached to addiction and mental illness. There's a whole generation and generations of lawyers that say, "Just toughen up. Be tougher."

You use the perfect term, which is generation. I hate to be more bid, but it's true. I'm a Boomer. A lot of these changes are going to happen until my generation is out of the profession. We're moving there. I'm not that old. Until the mastheads are the people who haven't put the bottles and didn't have the bar in their name partner office or in the cabinet who are used to sharing and recovering out loud, who understands that Alcoholics Anonymous or whatever 12-Step isn't the only way to recovery because in our profession, forget it. It's that way in the criminal justice system as well, especially in Texas, but it's more progressive in other places. Until that happens and we change out these generations, it's going to be lawyer by lawyer.

Even having these conversations and having people say, "I've been through this. This person has been through this. It can get better. This exists. It is a thing." It makes a difference.

For the curmudgeons, I'm going to get emails that say, "You're ragging on AA." I'm not. "You're ragging on 12-Step." I got sober in 12-Step. It saved my life. I, however, acknowledge that there are many paths to recovery and I would like others to acknowledge that as well.

Outside of recovery, setting aside things that need that level, what are some general ways that lawyers who are maybe struggling not to that level can build resilience, help, and support for themselves?

I can tell you what I did. I'm not a therapist. People may say, "You don't practice law anymore. It's easy for you." I will acknowledge that and that I found even the smallest amount of time for the things that I'm passionate about and for the things that give me joy by taking up singing. Don't ask me to sing. I find time to get the little things that give me joy and even emphasize the things that I feel obligated. Even just a percentage of the things that don't give me as much and that I can pull back through a little bit and push that time over to someone else can have a huge impact on my mental health.

I completely agree with all of that.

Everyone's life is different, every marriage and kids. They view their practice differently. It's not my place to insert myself into the life views of other people, but I can say what I did. I found slivers of the time and re-divided them for joy.

It's telling those stories. It's letting people know that you do need to find time and build resilience because the practice of law, even if you aren't suffering from any addiction, mental illness, or anything is draining, taxing, difficult, and stressful.

There seemed to be this notion that we have to fail to build resilience. It is not true. We can build resilience through the stories of others and learning from others. It's why I absolutely cringe when I see them in every LinkedIn post in the world like The Seven Habits of Mentally Strong People. Does that mean if you don't engage in those, you're mentally weak? This is the curmudgeon of the lawyer. There are levels of resilience that we can build. Everyone has a different level of resilience. Resilience can be built and learned. It can be learned without having to go through trauma.

You did mention LinkedIn. You're a social media presence and I know that you use it, but you also have a lot of criticisms of it. How do you navigate that, especially dealing in recovery and maintaining a healthy balance?

I'm not aware of any specific mental health criticism. I've criticized a LinkedIn police who trolls anyone who posts anything other than marketing, SEO, or whatever. Marketers and SEO, I love you. That's not what I'm saying. I'm saying the people who believe they have to have at least LinkedIn. Anytime someone posts tweets about mental health, they're on them. That's not for this. Shut up. You're your own freaking business. I block them. That's what the block is for. You don't have to see my posts, but I have criticism there.

I've seen you're engagement with people on Twitter. You do a good job of calling people out sometimes for insensitive comments and bad approaches to things. I appreciate it from you.

My view is just my view. Ten people have ten different views, but we do have something called stigma that is evidence-based. There are studies that if you use the word addict, it has a shaming effect. There are studies that if you use the word cokehead, as I get called all the time on Twitter but not so much anymore, if something goes viral and all the trolls come in, they are like, "You are cokehead," this and that," or whatever. I say, "No. "It was powdered cocaine." There is a stigma around crack. That's another story of how that happened racially. A lot of it I've learned to roll off me. Plus, because of my last name, it comes in more than maybe some others. If I let it bother me, I'd be back at Green Oaks for my third time.

You mentioned when we were talking about resilience and joy something that I want to cover here, which is you are an author, both of nonfiction talking about your journey, but more lately is fiction. How did you make that transition into writing fiction? It's pretty cool.

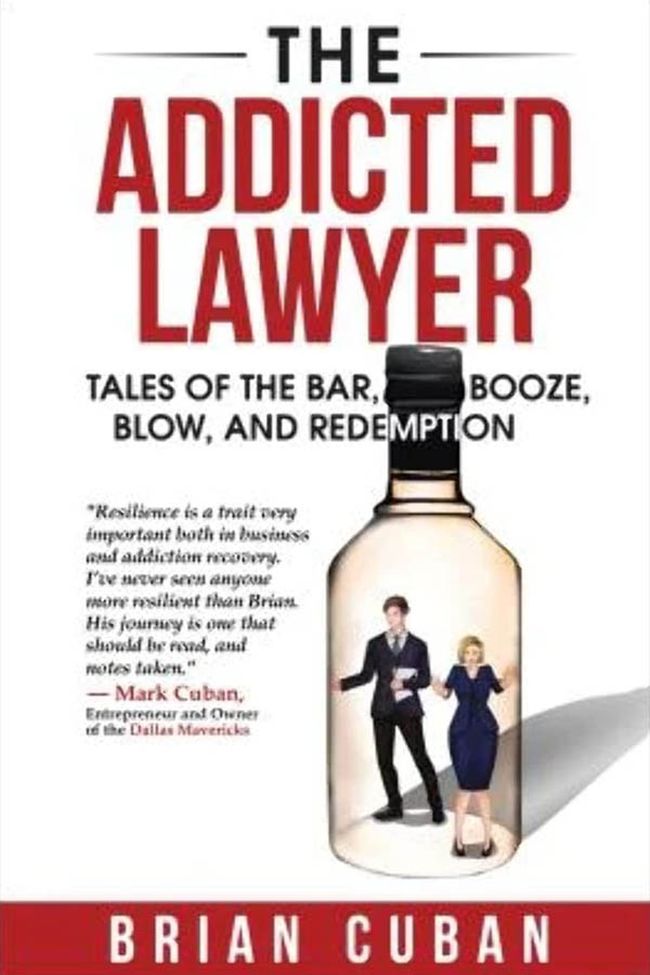

I wrote my first two books, the Shattered Image on body image and eating disorders and The Addicted Lawyer, which is a much more popular book within the legal profession and elsewhere. How many times can you tell your own story? I love to write. I just can't do it again. "The seven lessons I've learned from The Addicted Lawyer."

It sounds like a LinkedIn post.

I'm going to repurpose what I've had out there twice and I'm not going to do that because that's not the joy of writing. That's like I have to print something out for content. The joy of writing is creative for me. I had a dream. Here's how The Ambulance Chaser came about. I've been having this recurring dream and it's dark. If you're triggered by a dark dream, shut down the volume.

I had this recurring dream about growing up in Pittsburgh with one of my childhood friends. We're throwing dead bodies into a bonfire. I don't know why we're throwing them in, but we're throwing them in and they're naked. They're crackling. It's a giant Texas A&M bonfire. That's what writers do. We do these similes and things so you can envision it. Their eyes are staring back at me like the eight-ball cracked eyes. It's bulging. All of a sudden, the dream shifts to Brian as an adult. I wake up with this terrified feeling in my stomach. I wake up from the dream wondering if I've murdered anyone and why I haven't been arrested.

It went through many ideations, but the skeleton is in the closet. Time passes. The skeleton in the closet opened as an adult. It's not a new concept in fiction and thriller writing, but here's something I tell every beginning fiction writer. There are only about twelve thoughts in the world. Anything you watch whether it's TV, whether you read it, and no matter what genre, is going to be a variation of one of these thoughts. Romance had theirs. Thrillers has theirs, whether it's Grisham or Don Winslow.

It's almost like the hero's journey. Everything you want and everything you consume in the fiction realm is going to be one of these. You're not going to think up anything new. For Jason, it's a lawyer who was involved in a crime. It wasn't that crime but involved in a crime with a high school classmate 30 years prior. This girl is subsequently murdered and the bodies are discovered. Now, he's in his career and he's afraid that when it comes out that he was involved, it's going to bring him down.

His wife's the district attorney. He has a son and it's going to bring him down. What does he do? He's ultimately arrested for it. It was an old crime coming back to haunt a new adult. There is nothing new. The only thing that is new in fiction writing is great and wonderful characters. Also, interesting situations. You can do all the things, but you can have interesting situations and twists. Those are the new things to focus on because you're not going to think of a new plot.

I enjoyed it. I read it when it came out. I'll put my plug in for what that's worth. It's worth reading.

I'll give you an example. I'm writing a book called The Body Brokers. That's my second novel that I'm finishing up. It is not about feeling kidneys. It is about a murder that happens within the addiction community. The protagonist, Jason, the girl he's dating overdoses. He and her roommate go on this quest to solve and prove that overdose was not accidental. It takes them into the world of addiction body brokering.

What body brokering is, is our treatment facilities are bringing bodies. They don't try to help anyone. They bring in bodies. They put them through 30 days. The insurance runs out. They put them back out on the street to overdose and die. They bring in another body to fill the bed. They fill the insurance company. That is the general nature of body brokering. I got one of my guys looking at my manuscript. He says, "Did you know that Michael Williams, the guy who played Omar, had this movie The Body Broker? It's about this." I said, "Mine is different." There's nothing new.

When may we see The Body Brokers out?

For sure on 2024. I'm finishing up as we speak.

I want to ask you. That's quite a transition. You have written your own recovery-slanted books. I assume you found your groove and what worked for you as a writer in terms of being able to produce a book because that's a big job.

It was a learning process. Writing a memoir is not the same as writing fiction. I am fortunate to have a very good mentor who lives out in California. She's a very respected novelist and she doesn't tell me what I want to hear. It took me a long time. I was working on The Ambulance Chaser and sending her stuff. She was saying, "This is awful. Here's why it's awful."

It was because I didn't understand how to write fiction. I didn't understand that you had to read other fiction. I thought because I wrote a memoir, I could go boom. I had to stop and I began reading everything. I began reading legal thrillers and dramas. I began reading romantic novels, first-person, third-person, and all of these things. Also, BIPOC and figuring out what's bad and what I wouldn't do. Also, I figured out my voice.

I went through all of these processes to learn the art of writing fiction. In my opinion, it is impossible to learn to write fiction unless you read a lot of fiction. Before I started up, I passed that off to people who knows me. Now, I believe it with every bone in my body. It is impossible to learn how to write fiction or it's not going to be technically good fiction. You also have to do it. You have to get critiqued by people who aren't going to pardon it and tell you it sucks.

It may not be that brute and it may not be on the nose, but the worst mistake novice fiction writers can make is to send out their manuscript to people who are going to tell them how great they are. You need those people to tell you that you suck and why. Just a, "You suck," isn't helpful. If you want that, send it to a literary agent. They'll tell you, "You suck," when you have to get into the query process. It was brutal. They'll tell you, "You suck," in email. There are only two words and that's it.

This is good advice for practicing lawyers too.

This sounds a lot like legal writing and learning to be a legal writer as well.

Be critical and not a jerk. I say, "You suck," to make a point, but it's not helpful to say it and leave it there. You have to lay the groundwork for someone to get better.

It's constructive criticism.

Leaving it as, "It sucks," isn't constructive.

That's on the other side's briefing and not yours.

I do that and I send my manuscript out to people who may have intimate knowledge of a particular subject area. You may do that for legal briefs and appellate briefs. You do your own research. If I have a cop, I'll send it out to a cop, "Is this technically correct?" It's because you have what's known as authenticity. I have to know what is correct. I have to know what can happen, what always happens, and what can't or what never happens.

What never happened in terms of technical things could hurt your author authenticity. If I have a female doctor, I'll send it out to a female doctor because I need to understand to be sure I'm not usurping, or if it's a Black doctor or another person of color doctor, what reference can I possibly have for that? You had your targeted readers to make sure that you got it right.

Brian, one thing I can say, and I think I could speak for Jody on this, too, is we certainly admire your courage and sharing your journey. For many years, we both followed you. You've been very outspoken about your journey and not shy at all about helping others through the experiences that you went through yourself. We'll speak as lawyers and on behalf of the legal profession, too, to say thank you. It's a direct tie-in to some other conversations we've had on this show about TLAP specifically.

Also, about substance, alcohol abuse, and the things that lawyers do that are very self-destructive where they can't always help themselves, at least not without reaching that point that you described or that point of acceptance where you've got to say, "Yes, I need help." Thank you for that and thank you for talking through it with us. We're also interested in your career as a writer.

You are now on my email list whether you like it or not.

I'll be happy to see it when it comes and I look forward to reading it. It's our tradition on our show to leave each interview with an opportunity for the guests to offer a tip or a war story to our audience. With that in mind, do you have something that you'd like to say?

Let's take that off that time machine back to June of 2006. The Dallas Mavericks are going to the NBA championship for the first time. They're playing the Miami Heat. I hadn't gone into recovery yet. As you might expect, I was going to get some pretty good seats for those games. I also had the opportunity to get a couple of tickets for friends. I called up my brother and this is when we had paper tickets. My brother said, "Sure, Brian. Come on over."

I got the tickets. Do you think I gave them to my friends? No. You probably think I sold them on eBay for some astronomical amount. I was thinking like a lawyer. I didn't do that either because that would be disrespectful to Mark, to the team, or to myself. I took those two tickets and traded them to my cocaine dealer for $1,000 in cocaine. Selling them on eBay was disrespectful, but trading them to my cocaine dealer was perfectly acceptable. It's all the mind works in addiction.

My dealer shows up at my house. I was high class. He delivered. I gave him the two tickets. He gives me the giant bag of cocaine. I run up to my home office. I put it out on my desk. It's like I'm Scarface. I rub my nose in it. I line it out. I rolled up a $1 bill. Cocaine users were an ironic bunch, especially during pandemic times. You use the PURELL. You wash your hands, but we'll stick a $1 bill up our nose that's been used by God knows who and God knows what is on it. Go figure.

Cocaine had long stopped giving me the feeling of self-love and acceptance. Now, it's paranoia. I hear the cops outside. They weren't out there, but I'm paranoid. I hide the cocaine. I drive to a Home Depot where I buy electrical tape, a drill, and a saw. I drive back to my house and I take the drill and saw. I take the drill. I created these fake electrical outlets in the drywall and all the rooms in my house. I put the cocaine in smaller Ziploc baggies. I slapped it behind the drywall. I fill it up thinking I'm the smartest lawyer ever. I'm like the DEA, the cops, and the drug dogs who have never thought of that before.

I lined out some more and just pain and chain and paranoia again. I go back to those electrical outlets. I take it all back out again. I go to my master bathroom and flush it down the toilet. Now, it's $900 worth of cocaine. I get up the next morning and I'm thinking, "Did I flush my blow down the toilet? I'm an idiot. Who does that? There's another game tonight too." I call up my brother again. I got two more tickets for the game. I called my dealer. He shows up at my house. He said, "Dude, you did it all last night?"

I didn't want to tell him I flushed it down the toilet like a moron. I said, "Yes, I did it all. Give me more." "Here you go." It was rinse, wash, and repeat. I go back up to my home office. I lined it out. I get paranoid. I put it behind the electrical outlets again, and an hour and a half later, I take it back out and go to that same bathroom again. I drop to my knee like I'd done so many times, praying or hoping for someone or something to take away my shame or my pain and flush it down the toilet again the second night in a row. They say when Dallas flushes, it runs downhill to Houston. That was a common thing. In the morning news, it would always run the story about how the wastewater runs downhill to Houston.

That's a good one, Brian. Thanks for sharing. It gives us a little insight into the mindset of you at the time.

There are many. I was going hearings smashed and on cocaine. "Yes, motion denied." Again, I don't say that as badge of honor. Some readers are like, "How is this guy's name not in the back of Texas Bar Journal?" I wasn't disbarred and suspended, but it wasn't for the lack of trying. I'll leave it with that.

We're grateful that you shared all this and spent this time with us. Thank you so much.

Thank you guys.

The content of this article is intended to provide a general guide to the subject matter. Specialist advice should be sought about your specific circumstances.